The Oviraptor, a small but enigmatic dinosaur, has long been a subject of intrigue and debate among paleontologists. Its name, meaning “egg thief,” suggests a diet of eggs, but recent discoveries have added layers of complexity to our understanding of its behavior. Did Oviraptors actually eat eggs, or were they, in fact, protectors of them? The answer isn’t as straightforward as it might first appear, and it sheds light on the evolving science of paleontology and how dinosaur behavior is interpreted.

The Oviraptor: A Mysterious Dinosaur

Oviraptors were small, theropod dinosaurs that lived during the Late Cretaceous period, roughly 75 to 71 million years ago. Characterized by a beaked, toothless mouth and a distinctive crest on its head, Oviraptors were bird-like in some aspects, though they were not directly related to modern birds. Instead, they belonged to a group of dinosaurs called Oviraptorosaurs, which were closely related to dromaeosaurs and other theropods.

What makes Oviraptor especially fascinating is its association with dinosaur nests and eggs, which has led to its name—Oviraptor philoceratops, meaning “egg thief” of the ceratopsid. Fossils of Oviraptors were often found in close proximity to fossilized eggs, and early paleontologists speculated that these dinosaurs were egg thieves, raiding the nests of other species.

The Egg Thief Theory

For many years, Oviraptor’s reputation as an egg-eating dinosaur was cemented by the fossil evidence available at the time. In the 1920s, a fossil of an Oviraptor was discovered on top of a nest of Protoceratops eggs in Mongolia. The position of the dinosaur fossil—sitting on the eggs with its jaws open—seemed to support the idea that Oviraptor was raiding the nest and feasting on the eggs.

However, this interpretation was based largely on the assumption that the Oviraptor was guilty of egg predation, a conclusion that was consistent with its name and the fossil’s initial appearance. It wasn’t until more fossil evidence emerged that this theory started to come under scrutiny.

A Shift in Understanding: Protectors, Not Thieves

In the 1990s, a breakthrough in dinosaur fossil analysis led to a radical shift in the interpretation of Oviraptor’s behavior. New discoveries, including more fossils of Oviraptor and other related species, began to challenge the egg-thief theory.

One of the most significant pieces of evidence was the discovery of Oviraptor fossils in nesting positions that suggested a different role. In 1999, a fossil of an Oviraptor was found in a similar posture to its previous egg-associated find—but this time, it was on top of a nest of its own eggs. This new evidence strongly suggested that the Oviraptor might not have been an egg thief at all but rather a dedicated parent that was protecting its eggs.

Further studies on the nesting habits of modern birds, which are known to care for their eggs and young, began to inform how paleontologists interpreted fossil evidence. Birds and reptiles share many reproductive traits, and some modern birds, such as ostriches, have been observed guarding and incubating their eggs. The similarity between Oviraptor’s posture and that of modern birds led scientists to hypothesize that the dinosaur might have been protecting its own eggs, much like contemporary birds do.

Additionally, the arrangement of the eggs within the nests of certain Oviraptor fossils revealed that the eggs were likely cared for and protected, rather than eaten. The care and positioning of the eggs—often found in neat clusters, sometimes even with evidence of incubation—pointed more toward parental care than predation.

Reevaluating the Evidence

The shift in perspective regarding Oviraptor’s behavior has led to a more nuanced understanding of its lifestyle. Rather than being the egg thief it was once thought to be, the Oviraptor may have played a critical role in its ecosystem as a caregiver.

Several factors contribute to this new interpretation:

- Nesting Behavior: Oviraptor fossils found near or on nests of eggs suggest a protective stance, not one of predation. The fact that the nests were often associated with well-arranged eggs indicates that the Oviraptor may have been guarding them from other predators.

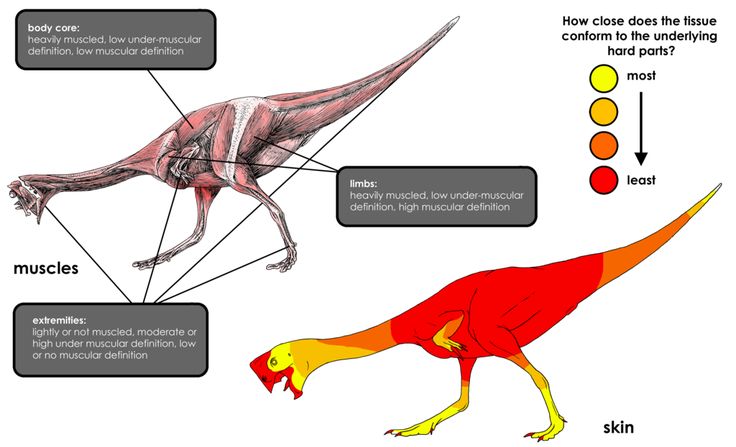

- Physical Evidence of Parental Care: In some fossils, signs of incubation behavior are present. The orientation of the body of Oviraptors found with eggs suggests a form of brooding, similar to how modern birds incubate their eggs.

- Diet and Anatomy: The beak of Oviraptor was adapted for a variety of functions, including possibly grasping and manipulating eggs, but there is no definitive evidence that its primary diet consisted of eggs. Its teeth were absent, which implies a diet that may have included small vertebrates, plants, or perhaps even some invertebrates, but not necessarily a significant amount of eggs.

- Broader Context of Oviraptorid Behavior: Other members of the Oviraptoridae family exhibit similar nesting behaviors, indicating that egg protection and parental care might have been more common within this group. This suggests that Oviraptor might not have been unique in its role as a guardian of eggs.

The Role of Oviraptors in Their Ecosystem

By examining the fossil record, scientists are learning that Oviraptors likely played a vital ecological role as protectors of their offspring. This suggests that, like many modern birds, Oviraptors were devoted parents that took an active role in ensuring the survival of their young.

Additionally, the new interpretation of Oviraptor’s behavior opens the door to understanding the complex evolutionary trajectory that led from dinosaurs to birds. The development of parental care in dinosaurs was likely a precursor to the behaviors seen in birds today, and Oviraptors offer a fascinating glimpse into these early stages of evolutionary history.

Conclusion: Rewriting the Story of Oviraptor

While early fossil interpretations suggested that Oviraptors were egg thieves, recent discoveries have led to a major revision of their behavior. Instead of raiding nests, it seems that Oviraptors were more likely to have been protective parents, guarding and nurturing their eggs.

This shift from predator to protector in our understanding of Oviraptor not only challenges our perceptions of this fascinating dinosaur but also enriches our broader understanding of dinosaur behavior and the evolution of parental care. As new fossils continue to emerge and technology improves, the story of Oviraptor will undoubtedly continue to evolve, offering even more surprises from the distant past.