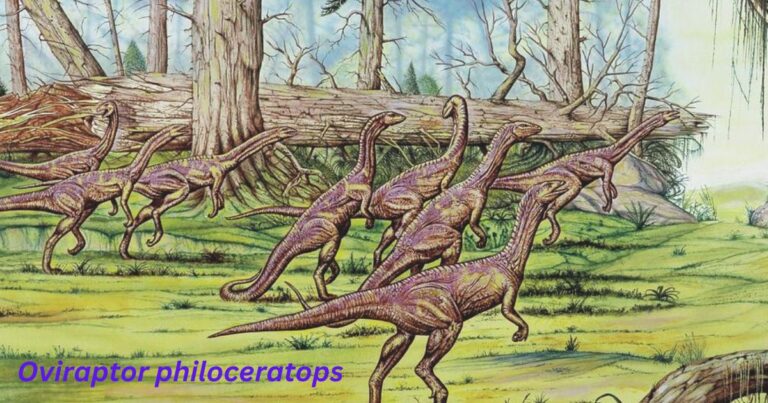

Oviraptors, a unique group of theropod dinosaurs that roamed the Earth during the Late Cretaceous period, have piqued the interest of paleontologists for decades. Known for their distinctive beak-like jaws and crest on their heads, these dinosaurs have generated numerous theories regarding their diet and feeding behaviors.

But what evidence exists to support our understanding of how Oviraptors fed? This article explores the fossil findings, anatomical features, and ecological insights that illuminate the eating habits of these intriguing creatures.

Fossil Evidence

One of the most compelling sources of information about Oviraptors’ diets comes from fossilized remains. The discovery of Oviraptor fossils alongside nests containing eggs has sparked significant debate about their feeding habits. Here are some key findings:

- Nesting Sites: Some Oviraptor specimens have been discovered in proximity to dinosaur nests. This has led to the theory that they may have preyed on the eggs of other dinosaurs. In particular, fossils found in Mongolia, including those of Oviraptors in brooding positions, suggest that these dinosaurs might have been guarding or scavenging eggs rather than exclusively raiding nests.

- Stomach Contents: In rare cases, well-preserved fossils provide direct evidence of diet. For instance, some Oviraptor specimens have been found with intact remnants of eggshell in their abdominal cavities, indicating that eggs were indeed a part of their diet. The presence of these fragments supports the idea that Oviraptors had specialized feeding behaviors tailored to consuming eggs.

- Associated Fossils: The discovery of Oviraptor fossils alongside small vertebrates and invertebrates can also provide insights into their dietary habits. These associations suggest that Oviraptors were opportunistic feeders, likely consuming a variety of food sources, including small animals and insects.

Anatomical Features

The anatomy of Oviraptors offers additional clues about their feeding strategies:

- Beak Structure: Oviraptors possessed a unique beak-like jaw that was likely adapted for grasping and manipulating food. This beak would have been particularly effective for cracking open eggs and extracting contents, allowing Oviraptors to take advantage of a readily available food source.

- Dietary Versatility: The overall morphology of Oviraptors suggests an omnivorous diet. Their beaks, coupled with robust limbs and flexible necks, indicate they could have easily switched between plant material and animal protein. This adaptability would have been beneficial in various environments.

- Posture and Locomotion: The bipedal stance of Oviraptors allowed for efficient movement across diverse terrains. Their agility may have aided them in both foraging for food and escaping potential predators. This adaptability suggests that Oviraptors were well-suited to exploit multiple food sources in their habitats.

Ecological Context

Understanding the ecological context in which Oviraptors lived also provides insight into their feeding habits:

- Prey Availability: The Late Cretaceous period was a time of great diversity in both flora and fauna. Oviraptors likely thrived in environments rich with small vertebrates, insects, and plant life, allowing them to adapt their diets based on available resources.

- Competition and Predation: Oviraptors coexisted with other theropods and herbivorous dinosaurs, which would have influenced their feeding strategies. Their ability to exploit different food sources would have minimized competition and allowed them to thrive in diverse ecosystems.

- Behavioral Adaptations: The potential for social behavior among Oviraptors, such as nesting in groups or foraging together, may have also impacted their eating habits. Such behaviors could increase foraging efficiency and enhance their ability to locate food sources.

Conclusion

The evidence supporting Oviraptors’ eating habits is a rich tapestry woven from fossil discoveries, anatomical features, and ecological context. While early interpretations suggested a primarily egg-centric diet, it is now clear that these versatile dinosaurs likely employed a range of feeding strategies.

The combination of fossilized remains, anatomical adaptations, and environmental factors paints a complex picture of Oviraptors as adaptable and opportunistic feeders, capable of thriving in the dynamic ecosystems of their time.

As research progresses and new fossils are unearthed, our understanding of Oviraptors’ diets will continue to evolve, revealing even more about these remarkable creatures from the age of dinosaurs. For more Oviraptors information check the dinorepeat.